For most of his career Menachem Begin was maligned as a terrorist, first when he commanded the Irgun (Etzel in Hebrew), the military arm of the Revisionists, troops committed to removing Great Britain from Palestine, and later when David Ben-Gurion and the Labor Party viewed him as an extremist opposition political leader, and even after he became prime minister, signed a peace treaty with the Egyptians, won a Nobel Peace Prize, yet then allowed Israel to become embroiled in a questionable war with Lebanon.

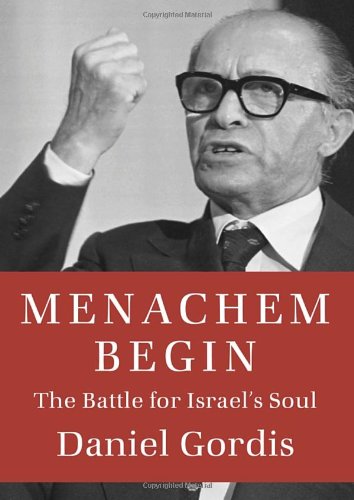

In this very readable biography, Daniel Gordis, senior vice president and Koret Distinguished Fellow at Shalem College in Jerusalem, sees Begin as a man whose priority was to defend and protect the rights of the Jewish people, whatever the personal cost.

Gordis provides excellent context to his understanding of Begin’s life and contribution to Israeli and Jewish history, frequently referring to other biographies, both English and Hebrew, in addition to general histories, Begin’s two books, The Revolt and White Nights, newspaper and journal articles and current Internet references, as well as interviews with people still alive who worked with Begin and knew him well. His style is sometimes didactic, sometimes melodramatic, even at times hagiographic, but there is no doubt in the reader’s mind where Gordis’s sympathies lie. Whatever methods Begin used, someone needed to carve out a home for the Jewish people and then keep it safe—what he perceives as Begin’s lifetime goal.

Gordis’s account of Begin’s life begins before he came to Palestine, as he describes the influence of his family, Polish nationalism, and especially his “master and teacher,” Ze’ev Jabotinsky, founder of the Betar movement and Revisionist opposition leader. Later, Gordis probes Begin’s relationship with Ben-Gurion, whom Gordis describes as “ever-pragmatic” as opposed to Begin, the ideologue. His description of the pre-state Yishuv is balanced and neutral, essentially providing the background for Begin’s policies during the 1940s when he led the Etzel in its armed struggle against the British. Often Begin cooperated with Ben-Gurion, who was then directing the Haganah, the military arm of the Labor party. In this respect, Begin could be considered a moderate, since he was committed to preventing any kind of civil war among the Jews. But according to Gordis’s sources, the Haganah often pulled out of planned operations at the last minute, leaving Begin to take sole responsibility. This was true, for example, both of the 1946 King David hotel bombing and the 1948 Deir Yassin village “massacre,” accounts that in standard histories of Israel always attribute blame to the “terrorist” Begin.

Gordis’s account of the 1948 Altalena affair focuses on the many misunderstandings between Ben-Gurion and Begin, each convinced his actions were both necessary and appropriate. But two things stand out: the sense that Ben-Gurion saw the arms shipment not only as the act of an opposition leader who was beginning to become a serious rival, but also perhaps as an opportunity to kill Begin under the cover of massive gunfire. Ben-Gurion went even further, calling the Etzel and its leader part of an “evil armed gang.” Though four years later Begin tried to defend himself in The Revolt, explaining the necessity of bringing arms to the then struggling new state, his reputation suffered terribly, both in Israel and in the United States. Gordis notes, however, that in 1965 Ben-Gurion finally admitted that perhaps he had been mistaken.

Similar differences of priorities surfaced in 1951 around the issue of receiving monetary compensation from Germany as a form of “reparations” for the lives lost in the Holocaust. On the one hand, Ben- Gurion, as prime minister, wanted to accept the money to help absorb the massive wave of immigrants coming both from Europe and Arab lands. On the other hand, Begin viewed the issue in terms of hadar, the concept of dignity that Jabotinsky had defined as essential for the Jews, and fought hard against receiving the money. Gordis adds his own interpretation, claiming that this was when Begin first engaged in “a battle for Israel’s soul,” one in which he emerged as the political voice representing Jewish memory as an inseparable part of Jewish survival––a concept echoed in much of today’s political discourse.

Gordis describes Begin’s rise from outsider to prime minister relatively briefly, albeit always within relevant context and stressing the book’s central theme: that while Begin was working within the Israeli political framework, he was first and foremost acting as a representative of the Jewish people. Among his first acts as prime minister was initiating the rescue of Ethiopian Jews, as well as 4,000 Jews in a Damascus ghetto. Though not personally observant, Begin brought the ultra-Orthodox parties into his coalition and grounded El-Al planes on the Sabbath, making the government more Jewish both in style and substance. But his major contribution was the one that brought him the Nobel Peace Prize, responding positively to Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Sadat’s peace overture and entering the negotiations that led to signing the 1979 peace treaty with Egypt.

The process was not easy. American president Jimmy Carter leaned much more heavily on Begin than on Sadat and seemed unable to comprehend Begin’s refusal to surrender Judea and Samaria (the “West Bank”) to the Palestinians. Reading Gordis’s account of the negotiations before and during the meetings at Camp David sounds eerily like the reports of the recent United States’ mediated negotiations, with many of the same issues still unresolved.

Not only do the topics discussed at Camp David sound remarkably current, so also do the factors that entered into Begin’s decision to bomb the nuclear reactor in Iraq in 1981. In what seems like a precursor of the controversy today between Israel and the United States Begin consistently repeated that either the United States would bomb the reactor at Osirak or “we shall have to.” Well aware of the potential for world condemnation for such an Israeli attack, he was willing to take the risk in order to protect the Israeli people—and so, from his perspective, prevent another Holocaust.

Critics of Gordis’s perspective of Begin can justifiably point to many places in the narrative that reflect a conservative bias. The one chapter where Gordis allows himself to present a range of opposing views relates to Israel’s entry into, and conduct of, the 1982 war in Lebanon. He acknowledges that the worldwide public opinion shift in favor of the Palestinians, accompanied by a decline in support of Israel, began as the war in Lebanon dragged on, culminating in the Sabra and Shatila refugee camp massacres. Though Begin’s defense minister, Ariel Sharon, did not fully inform him of events as they were taking place, Begin took personal responsibility for the tragedies. The Nobel Peace Prize winner lost the moral high ground.

Much of the last decade of Begin’s life, after he had resigned as prime minister and retired into almost complete seclusion, still remains a mystery. He was now a widower and sorely missed his wife and lifelong companion. His health, which had never been good, deteriorated even further. Perhaps, as New York Times correspondent Thomas Friedman wrote, Begin “seemed to have tried himself [for the events in Lebanon], found himself guilty and locked himself in jail.” Yet when he died in 1992, more than 75,000 mourners lined the streets of Jerusalem, joining the funeral procession to the Mount of Olives where, at his request, Begin was buried among the veterans of Etzel.

Perhaps the most surprising chapter in Begin is the Epilogue, where Gordis compares the American and Zionist revolutions, and assesses Begin’s contributions in establishing a Jewish state in relation to those of Ben-Gurion. In 1958, Begin himself referred to the American Revolution as a way of justifying Etzel’s contributions to winning the Jewish state. Eighteen years later, as he commemorated the thirty-fifth anniversary of Jabotinsky’s death, Begin quoted Thomas Jefferson’s observations that the “the tree of liberty must be refreshed from time to time with the blood of patriots and tyrants.” Both were reminders that while Ben-Gurion wanted a Jewish state, it could be argued that the actions of the “tyrannical” Etzel actually made it happen.

Why, then, for many Israelis and Diaspora supporters, is Begin’s name still associated with terrorism? Gordis concludes that Begin’s Jewish worldview led him to understand that life can be a messy business, that one often does not win the peace without fighting, and being willing to die. This, Gordis believes, is a legacy more complex than most people today are able to comprehend. By writing this book he gives us another perspective of Begin that may help many understand what he did and why, how one can staunchly defend the rights of one’s own people—and yet still yearn for peace with others. In many ways, Gordis suggests that Begin’s life can serve as an inspiration for the present.

No comments:

Post a Comment