In the tradition of Jared Diamond's best-seller Collapse (2004) and Simon Winchester's Atlantic (2010) comes Jack E. Davis' nonfiction epic, The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea, which strives both to celebrate and defend its subject — the Gulf of Mexico. Its Texas coastline is featured prominently in these pages. Detailed and exhaustive, written in lucid, impeccable prose, The Gulf is a fine work of information and insight, destined to be admired and cited.

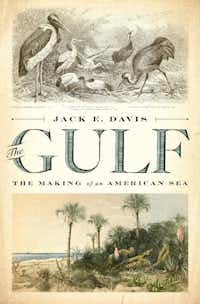

The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea, by Jack E. Davis

Liveright

It begins with a sweeping history of the early inhabitants, from paleo-Indians dating from the end of the Ice Age up to the arrival of Europeans. Davis then naturally shifts his focus to developments after the discovery of the "New World," particularly the early expeditions of Hernando de Soto and the exploits of Alvar Nuñez Cabeza de Vaca.

According to both historic accounts and archaeological studies, Florida's Calusa culture thrived on the bounties of the sea coast, which supported a healthy, successful and vigorous population —one that collapsed in part from the introduction of European diseases, and the steady influx of first the Spanish and then the English.

Along the Texas coast the Karankawa — a tribe made famous by both saving and capturing Cabeza de Vaca in 1527 — were in a similar position. That they were essentially driven to extinction echoes a familiar lament in the book: Exploitation was deadly for humans and animals alike. Davis' description of the 19th century plume industry, which devastated bird populations, mainly snowy egrets but other species as well, for fashion adornments, is particularly shocking and instructive.

A pod of bottlenose dolphins swims under the oily water of Chandeleur Sound, La., in 2010, after the Deepwater Horizon explosion.

(DMN file/AP Photo/Alex Brandon)

In the prologue Davis argues his goal is not to be a doomsayer: "The Gulf and its history — its biography, [French scholar Fernand] Braudel might say — should be celebrated, not mourned." Yet there is much to lament: Chapters 10 and 11 focus on the Gulf oil industry, primarily Texas and Louisiana, and its legacy of financial success and environmental catastrophe, from the Spindletop oil gusher of 1901 on: "Since the Deepwater Horizon tragedy of 2010, oil has hijacked the Gulf's identity. It frames how we — from journalists to policy makers, even scientists and tourists — perceive the American sea."

Development has brought beautiful hotels and tourist accommodations from Miami to South Padre Island, ruining wetlands and wiping out crucial wildlife habitat. We've overfished the waters, wiped out bird populations, and filled the soil and water with toxins. "The bottom line is that the Gulf has become less and less a fishers' sea than an industry's sea."

At times The Gulf suffers from the same flaw of several other excellent volumes of nonfiction, including Andrew Ross Sorkin's Too Big to Fail (2009), and Thomas Piketty's Capital in the 21st Century (2014): Davis looks at the Gulf from seemingly all relevant angles: fisheries, oil production, tourism, history, ecological history, pollution, development and much more. The approach is encyclopedic. Admirable, yes, but a bit exhausting. The historical breadth makes for a book chock-full of fun facts, such as how in the early years of European exploration they had much trouble actually finding the great Mississippi River; oil from Spindletop sold at 3 cents a barrel in 1901; and after World War II the U.S. military used parts of Gulf islands to dispose of munitions, not considering the environmental havoc it could cause.

Vessels assist in the drilling of the Deepwater Horizon relief near the coast of Louisiana at sunset in September 2010.

(DMN file/AP Photo/Patrick Semansky)

Chapter 13 focuses on hurricanes, starting at the Galveston's Great Storm of 1900 (in which some of my own ancestors perished): "No so-called natural event has killed as many people — more than eight thousand, according to the National Hurricane Center . . . more than the combined tallies of dead in the 1889 Johnstown flood and the 1906 San Francisco earthquake. "

The story continues through the storms of the 50s and 60s (Betsy, Carla and Camille) to Katrina, Ivan and their aftermaths. His summation of the current state of the Gulf's health is a gloomy one, in which "natural" disasters are exacerbated by bad economic and environmental policy decisions: "Louisiana has been declared a 'petrocolonial' state, and it's hard to argue with that assertion. The legislature almost always votes the industry's calling, and the courts rarely decide against it."

But all is not lost. He chooses to end this eloquent tome with an upbeat warning: "We cannot destroy or control the sea, although we can diminish its gifts."

No comments:

Post a Comment