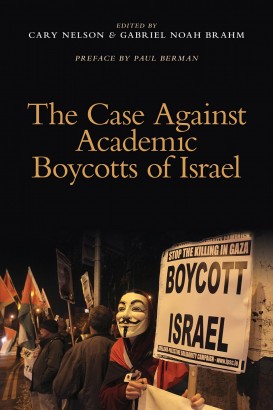

The Case Against Academic Boycotts byCary Nelson & Gabiel Noah Brahm (eds.) Wayne State University Press, 2014. pp. 552

The editors deserve major kudos for having compiled an impressive anthology featuring contributions in opposition to the deeply sordid, yet potentially potent, Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions (BDS) movement. Underlining the pervasive presence in the contemporary discourse of academic life in North America and – quite likely – most English-speaking countries is the fact that the target of these powerfully negative actions is ubiquitously known and needs no further specification to any audience. It is not Russia, not either of the Koreas, not China, not Iran, not Syria, not Britain, not Germany, not the United States – it is solely the State of Israel. The agenda for this large book is beautifully set by the brilliance of Paul Berman’s preface which, confirming yet again its author’s vast knowledge and elegant writing, shows how ‘the anti-Israel boycott has proved to be, ideologically speaking, the world’s most adoptable boycott – a boycott that, without the slightest embarrassment, changes its costume every few years in order to present itself as Muslim, Christian, supernaturalist, right-wing, left-wing, liberal, secular, and sometimes all of the above … as if no single doctrine or philosophy or theology or geographical perspective, but only the lot of them ensemble, could possibly sum up the justifications for conducting the boycott, so various are Israel’s sins.’

While some contributions – most notably one of Ilan Troen’s two – highlight both synchronically and diachronically the abundance and diversity of boycotts of Israel and Jews invoked by Berman’s characterisation, it is evident that the major thrust of virtually all presentations concentrate on the contemporary situation in American post-secondary education and thus on a decidedly left-wing version of this phenomenon. Indeed, as Cary Nelson correctly points out in his introduction, boycotting Israel as a solid manifestation of detesting its very existence has become arguably the single most potent marker of being of the left today. He quotes one of the global left’s most cherished gurus, the Italian philosopher Gianni Vattimo, who states the obvious that, ‘by now, anti-Zionism is synonymous with leftist world politics.’ Even if one is explicitly and actively anti-racist and anti-sexist, opposed to oppression, favours economic equality, fights for workers rights, actively supports the LGBT community, advocates strict gun control, stands for ecological reforms; one will be at best a very suspect, indeed even an unwelcome, member of what constitutes today’s left and being progressive without having decidedly and explicitly anti-Zionist views.

Opposition to Israel has mutated into the most important common denominator – the core, as it were – of what it means to be a leftist, a progressive in contemporary North America, Western and Northern Europe, the Antipode, in short the liberal democracies of the advanced industrial world. As I argued in my book Uncouth Nation, together with anti-Americanism, anti-Zionism has become the litmus test par excellence for being of the left in today’s world. These twin convictions have become the left’s core lingua franca. Nowhere is this sentiment and conviction more pronounced, indeed solidly hegemonic in the full Gramscian sense, than in the universities of these countries, particularly their humanities departments.

The book has six parts. The first, entitled ‘Opposing Boycotts as a Matter of Principle’ features a number of fine pieces, none more than by Martha Nussbaum, whose passionate opposition to boycotts is presented in a sober style full of conceptually compelling insights. Harnessing her expertise on the Indian state of Gujarat in which hundreds, possibly thousands, of Muslims were slaughtered, pogrom-style, in 2002 under the aegis of the then Governor Narendra Modi, now India’s Prime Minister, Nussbaum shows that nothing comparable to the boycott of Israeli universities and academics was ever even contemplated, let alone initiated in that instance. Indeed, as I also discussed inUncouth Nation, it was telling that France’s most popular anti-globalisation activist and progressive hero, Jose Bove (needless to say a fierce opponent of Israel) chose to travel to Ramallah at this exact time instead of Ahmedabad, Gujarat’s largest city and site of some of the worst anti-Muslim pogroms by Hindu mobs. Nussbaum also offers helpful characterisations of alternate measures to boycotts such as censure, for example, and further differentiates between economic boycotts which are clearly targeted (like those of South Africa and of Nestle), thus not only effective but also acceptable to Nussbaum; symbolic boycotts, like those invoked against Israel, which she finds useless and morally unacceptable because in essence they only have one purpose: that of wholesale vilification which can easily lead to false stigmatisation.

However, reading Russell Berman’s ensuing piece, one clearly gets the point that this indeed might well be the current aim of Israel boycotters. Worse than that, Berman argues forcefully that, ‘the boycott has let the genie of bigotry out of the bottle.’ Thus, one is hardly surprised to read that one particularly committed advocate of the boycott resorted to ‘Jew counting’ – n.b. not ‘Zionist counting’ – at, of all places, The Nation, coming to the conclusion that there were too many. (One can safely assume that had this person confined her objectionable activity to the counting of ‘Zionists’ at this publication, the tally would have been most assuredly nil.)

Part Two of the book focuses entirely on the American Studies Association (ASA)’s recent vote to boycott Israeli institutions of post-secondary education. Sharon Ann Musher’s detailed insider account of this sorry affair is particularly noteworthy because her well-researched and lucidly written piece reveals emphatically the BDS movement’s tactics and intent; presenting an important case study of a particular instance that stands for something much larger.

Part Four features five essays on the Israeli Context, two of which written by the aforementioned Ilan Troen: one analysing historical and ideological sources of the boycotting of Israeli universities; the other offering fine empirical evidence on the Israeli-Palestinian relations in post-secondary education which, as I fully expected, presents a much more sober, if far from rosy, account of realities on the ground than the Manichean bombast that have become the tenor of the British and North American academic left over the years would have us believe. In Part Five, Cary Nelson presents an admirably lucid and comprehensive history of Israel in a short essay of 50 pages. Lastly, in Part Six, the editors have assembled a helpful dossier of important documents on the boycott, featuring the ASA’s final resolution and debates on this topic involving the much larger and more significant Modern Language Association, in which both of this anthology’s editors assumed centre stage.

But it is Part Three, entitled ‘The BDS Movement, The Left, and American Culture’ which, to me, harboured far and away the most important and conceptually far-reaching contributions. It features a truly impressive critique of Judith Butler’s work by Cary Nelson. Measured in tone, exhibiting no polemics at all, Nelson’s detailed and lengthy text is the very best rebuttal of Butler’s views in the context of BDS that I have yet to read. The contributions by Mitchell Cohen, Kenneth Marcus, and Nancy Koppelman, are excellent. But I would like to single out three contributions that I found particularly interesting and immensely helpful.

To my knowledge at least, Tammi Rossman-Benjamin offers the first concrete numerical evidence for a phenomenon that I have observed for years, wondered about repeatedly, but have never quite seen so starkly exposed: that the vast percentage of the faculty boycotters on American campuses – 86 per cent! – belong to the humanities (49 per cent) and the social sciences (37 per cent), with only 7 per cent per cent affiliated with departments in engineering and the natural sciences. Of the 938 boycotters whom Rossman-Benjamin’s meticulous research has unearthed, 192 (21 per cent) are in English or literature departments; 96 (10 per cent) in ethnic studies; 68 (7 per cent) in history; 65 (7 per cent) in gender studies; 53 (6 per cent) in anthropology; 44 (5 per cent) in sociology; 39 (4 per cent) in linguistics and languages; 33 (3 per cent) in American studies; and 32 (3 per cent) in Middle or Near East studies. Why would a professor in an English department at an American university be so much more likely to support BDS than their counterpart in – say – sociology, or even Middle East studies, never mind their colleague in economics, the natural sciences or any of the professional schools be they business, law or medicine? In search for an answer to this question, Rossman-Benjamin examined the online descriptions of the research interests of several English professors who have endorsed the boycott of Israel. Here she found a preponderance of four analytical categories that defined their research: class (including terms such as Marxism, Critical Theory); gender (including terms such as Feminism, Sexuality and Queer); race (including terms such as Ethnic, Native, Indian, African, Black, Indigenous, Asian); and empire (including terms such as Post-Colonial, Imperialism, Subaltern, Alterity). Applying these categories to her larger sample, Rossman-Benjamin then conducted a comprehensive analysis of the research interests of all 143 professors of English (excluding the 49 faculty members in various literature departments apart from English that comprised the aforementioned 192): 92 per cent have research interests that include one or more of the aforementioned four categories.

The reasons for this being the case is best answered by Sabah A. Salih’s superb contribution entitled ‘Islamism, BDS, and the West’. Tout court, the author correctly anchors the beginning of this entire discourse with the advent of the New Left, which shifted the axes of theory and practice from the old Left’s proletariat as the subject of history and prime agent of salvation to that of third world peoples. This also entailed a much more comprehensive reorientation of progressive politics from extolling the Enlightenment as virtually all major agents of the old Left did with gusto to its total dismissal. Indeed, for the New Left, the Enlightenment – and its main global representative, ‘the West’ – mutated into the all-powerful oppressor which had to be confronted on all fronts, with new agents of progress and revolution, none more potent than Third World liberation movements of whatever ideological bent. Few, if any, became more beloved for the new progressives than the Palestinians, victims of the Jews, who, a priori suspect as paragons of the Enlightenment, became doubly evil by virtue of attaining power in a ‘settler’ state and thus becoming exhibit A of a Western-implemented (neo) colonialism at the behest of the source of all evil – the Great Satan as it were – called the United States of America. I have long argued that a profound and socially accepted discourse of anti-Americanism, that is legitimate because it is directed at a powerful entity, lay at the foundation of the Western Left’s hatred of Israel. With the axis of analysis shifting from the economy and capitalism to culture and power, the locus of progressive politics in the academy shifted to the humanities. As Salih presents convincingly, nothing provided a more potent booster for this development than Edward Said’s Orientalism. Published in 1979 this book’s pervasive presence and continued influence in many fields of the humanities and the ‘soft’ social sciences can simply not be exaggerated.

So what does all this mean? An excellent piece by Samuel Edelman and Carol Edelman hits the nail on its head. Appropriately entitled ‘“When Failure Succeeds”: Divestment as Delegitimation’ the authors demonstrate that the actual effects of BDS have been less than negligible. Very few universities, associations, institutions have actually taken even the most rudimentary steps to implement any such policies, let alone carried them out to full completion. But, as the authors also point out, that may actually not even be the real purpose of the boycott’s exercise. Rather, it is to delegitimise, to stigmatise the existence of Israel in an incrementally creeping process – in a sort of Chinese water torture manner, one steady drip at a time.

And let’s face it: that exactly is the crux of this entire controversy and the source of its potent acrimony on both sides of the issue. It is not about Israel’s policies, as boycotts were in the case of South Africa and Nestle and other concrete cases; it is about Israel’s existence. This is not to say that some of Israel’s awful policies – the ones that use the guise of security to enhance territorial gains for purely nationalistic and/or religious reasons – have not added fuel to the fire of the boycotters. There is no question that some of Israel’s misguided policies have fostered an outer circle of willing sympathisers and normative fellow travellers to the core of the boycotters and their agenda. The former might disappear with changed Israeli policies, but the latter never will. And therein lies yet another singling out of Jews in their troubled history.

No comments:

Post a Comment