Jews Praying In The Synagogue on the Day of Atonement by Maurycy Gottlieb (Tel Aviv Museum of Art) The Israel Book Review has been edited by Stephen Darori since 1985. It actively promotes English Literacy in Israel .#israelbookreview is sponsored by Foundations including the Darori Foundation and Israeli Government Ministries and has won many accolades . Email contact: israelbookreview@gmail.com Office Address: Israel Book Review ,Rechov Chana Senesh 16 Suite 2, Bat Yam 5930838 Israel

Sunday, April 30, 2017

The Story Banned by Israeli Schools.....All the Rivers by Dorit Rabinyan (Random House)

An excerpt from the award-winning story of young, forbidden love between an Israeli woman and a Palestinian man.

We turned back to Broadway and headed south this time, from Twenty-eighth toward Tenth Street. We walked briskly, purposefully, alert to every metallic glimmer on the sidewalk. Down to Union Square, right, then left, and down Sixth Avenue, Hilmi taking large, energetic strides, paving a path for us through the crowds, and me behind him. As we searched among all the moving feet in case the keys had fallen on the way, we passed the same window displays and brightly lit alleys we’d seen before, the same doorways of shops and giant department stores, the same lines of trees and shady treetops and office buildings, now on our left, dark and locked.

The repeated sights brought a replay of our chatter, everything we had said an hour earlier going up Broadway, but the conversation also proceeded in reverse order, from end to beginning. Like playing a record backward and imagining subliminal messages emerging from the garbled sounds, or rewinding a cassette tape with its squeaky distorted playback, so my sense of guilt accelerated and grew sharper, and my heart pounded faster, matching the beat of our hurried steps. In retrospect, I noticed all the things I’d missed before, when I’d talked longingly about the sea in Tel Aviv and raved about my diving adventures in Sinai. I recalled how he’d kept quiet here, or hadn’t responded there, and I remembered a serious look he’d given me at this intersection, and how right here, when we stopped to gaze at the moon, he’d sighed deeply.

I was now attuned to every tone of voice and every expression. I thought twice before speaking, phrased things carefully to prevent any misinterpretations that might arise from my English. I nodded vigorously whenever he spoke, and laughed too loudly at his jokes. I scanned every inch of the sidewalk, throwing myself into the search for the keys in an attempt to compensate, to repair, to restore what had been lost—a spontaneity, a lightheartedness that was no longer there.

Kosher-Kosher-Kosher-Kosher. All the delis in downtown Manhattan seemed to have become kosher, and I spotted more and more menorahs lit up among the Christmas trees in the shop windows. Two ultra-Orthodox men with streimels and bobbing sidelocks came toward us, and farther down the street we could hear thunderous darbuka drumming from a tattoo and piercing den. Another branch of “Hummus Place,” another corner store selling newspapers and magazines in foreign languages, including Maariv and Yediot America alongside papers with Arabic headlines.

We entered the desolate darkness of a pub and asked to use the bathroom. While I stood outside the single stall in the women’s restroom waiting for someone to emerge, I wondered whether Hilmi, in the men’s room on the other side of the wall, was also reading the word in the little door lock—Occupied—and thinking about the occupation.

My series of knocks on the stall door produced a muffled voice from inside: “Just a minute.”

Alone now, I replayed what had almost happened back when we’d stood at a crosswalk and he’d suddenly looked at me, bathed in a reddish glow from the light. His eyes had lingered on my face, focused on my lips, and I was struck by a certainty that he was about to lean over and kiss me. I remembered the wave of air that had hung between us, and the trembling, almost-happened second that ended abruptly when the light changed to green and everyone around us stepped onto the street. I didn’t even realize I was banging on the door again.

“Just a minute!”

I stifled not only the urge to pee but also the pleading voice that burst into my head as though it had just been waiting for its chance to get me alone: What do you think you’re doing? You’re playing with fire. Tempting fate. Don’t you have enough problems? What do you need this for? I suddenly felt a need to see what I looked like, how I’d looked to him at that crossing. There was no mirror above the sink or on the paper towel dispenser, but I caught myself in the dark glass on the emergency supply cabinet, and my face looked cloudy and tormented.

***

When was it? Five or six years ago. I was on a jitney bus in Tel Aviv. I got on at the old Central Bus Station, and we hadn’t even made it around the bend to Allenby Street before we got stuck in a huge traffic jam. It was midday and the jitney was almost empty. Two passengers sat in the back, and one woman in front of me. At some point the driver got sick of the music on the radio and started flipping through fragments of verbiage and snatches of melodies until he tuned in to a religious station, Arutz Sheva or something like that. He paused there, and actually turned up the volume when an announcer yelled, “Dozens of young girls, Jewish women, every single year!”

It was the deep, warm voice of an older Mizrahi man with impressively enunciated glottal sounds. “Daughters of Israel! Lost souls!” he kept shouting. “Seduced to convert to Islam, God have mercy! Married off to Arab men who kidnap them and take them to their villages, drugged and beaten, where they are held in conditions of hunger and slavery, with their children! In central Israel, in the north, in the south . . .”

Through the dusty window I could see a trail of blue buses crawling toward Allenby in the summer light. The voice went on: “Sister’s Hand, an organization founded by Rabbi Arieh Shatz, helps rescue these girls and their children and bring them back to Judaism, into the warm embrace of the Jewish people. For donations or to reach the emergency hotline, call now—” Then I heard the passenger in front of me talking to the driver. I remember her telling him about her sister-in-law’s daughter, who was one of those women who’d fallen in with an Arab: “Some guy working construction near where they live in Lod. He’s from Nablus. . . .” “Oy, oy, oy,” I remember the driver responding with a gasp. Then he clucked: “God help us.”

“And he doesn’t look Arab at all!” the astonished woman added. The driver clucked again: “Those are the ones you really have to watch out for.”

She told him how the man had pursued the girl, spent lots of money on her at first, showered her with gifts. Her poor sister-in-law had begged the girl not to go with him. She’d cried her heart out. But nothing helped. She dated him for a few months and was already pregnant when they got married. “Now she’s rotting away there in Nablus, you can’t imagine. . . .”

“Dear God . . .”

“Two kids and pregnant again.”

“God curse them all.”

“She hardly has any teeth left, he beats her so badly.”

“Those animals! For them to nail a Jewish woman is a big deal.”

Someone flushes the toilet loudly in the stall. When the door finally opens, a long-legged blonde emerges. She mumbles something and gestures back at the floor. “Watch out,” she says loudly, pointing to a puddle at the foot of the toilet, “it’s slippery in there.”

I tiptoe in. As I squat on the seat, the loud hum of the tank refilling from the pipes in the wall mingles with the girl’s voice in my ears: watchoutitsslipperyinthere, watchoutitsslippery . . . I wonder if it’s a sign: her warning, the light changing at the critical moment, the keys. Yes, the lost keys: that’s a sign that I shouldn’t go to Brooklyn. It was divine intervention that knocked those keys out of his pocket, the hand of God protecting me from what might happen, reaching out to put an end to this story before it begins. A bad feeling flickers inside me again, that alternating glow between push and pull, between attraction and fear.

I walk out and wash my hands, resolving to help him find his keys and then go home. When we get to Café Aquarium I’ll say goodbye warmly, maybe we’ll exchange phone numbers, a peck on the cheek, and I’ll head straight home. But even as I wipe my hands on a paper towel and tell myself these things, I know they will not happen. I know they are hollow words meant to calm me. I walk out of the pub and he is waiting for me. A serious smile shudders between us, and I cannot help noticing his eyes locked on my lips. His curls glow like flames in the red light at the crosswalk.

From the Book, ALL THE RIVERS by Dorit Rabinyan. Copyright © 2017 by Dorit Rabinyan. Reprinted by arrangement with Random House, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House, Inc. All rights reserved.

Saturday, April 29, 2017

Essential African Novels

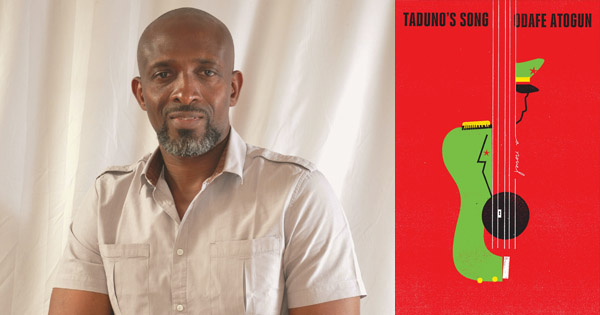

Odafe Atogun

Photo Credit: Adebayo Adekunle

In Taduno's Song, Nigerian author Atogun combines a retelling of the Orpheus myth with a Kafkaesque meditation on identity in a powerful novel about a musician who runs afoul of the ruthless Nigerian government. His picks are a Nobel winner and a debut novelist.

1. Disgrace by J. M. Coetzee - In Disgrace, a middle-aged professor of Romantic poetry finds himself observing the ritual of a relatively happy life in which his sexual needs are adequately taken care of. He appears to be content but secretly yearns for more. Disturbed by the knowledge that his old charms have fled him, he finds comfort in an anxious flurry of promiscuity. An enchanting liaison with a prostitute is followed by a reckless affair with a young student, and his "ordered" existence becomes shattered.

Coetzee weaves with brutal, admirable grace a troubling story in which the professor, in a bid to escape the consequences of his action, finds refuge in his daughter’s isolated smallholding in post-apartheid South Africa where retributive violence is stoked by racial conflicts. There the turn of events will afflict him with punishments worse than he could possibly bear, leaving his innocent daughter a victim; leaving also, the lasting message that retribution must be avoided if we are to ultimately escape its ugly legacies. In the incontrovertible disgrace of a once-brilliant professor, lessons are there to be learned for a nation torn by racial divisions.

2. Season of Crimson Blossoms by Abubakar Adam Ibrahim - Season of Crimson Blossoms is a beautiful-sad story told with great artistry. Against a backdrop of tragic family histories brought about by ruthless politicking and religious extremism, Binta, a devout middle-aged Muslim widow, and Reza, a young weed-smoking gangster, begin an illicit affair.

Haunted by the painful memory of loss in a hypocritical society which uses religion to promote hatred and violence, Binta experiences a primal desire to save her lover from a life of crime. But is it love or the quest for redemption that emboldens her to listen to her heart for once? A combination of both, maybe?

Whatever, it is an affair that foretells grave danger, for Binta especially. But already held a prisoner by the hopeless yearnings of her own heart, she finds it impossible to apply the brakes. And as the affair festers and consumes her and her lover, Binta realizes that she is living in a society that will never allow her to find love, even if she chooses to steal it. As for Reza, he is confined by society never to find fulfillment, not even redemption.

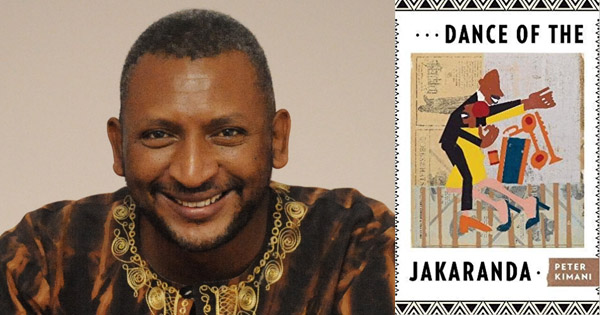

Peter Kimani

Photo Credit: Yusuf Wachira

Highlighted by its exquisite voice, Kimani's Dance of the Jakaranda illustrates the discordant history of East Indians in Kimani's native Kenya, centered on the construction of a railroad connecting Lake Victoria and the Indian Ocean at the end of the 19th century. Kimani's selections are a what he calls a "deceptively simple novel" and Ngugi wa Thiong'o's influential novel about the effects of political independence on ordinary Kenyan citizens.

3. Coming to Birth by Marjorie Oludhe MacGoye - This deceptively simple novel is about a young woman, coming of age at a time of rapid social change in Kenya. The wind of change is blowing through the land as Kenya gains independence and Paulina, only 16, arrives in the city to join her new husband, Martin. A recent arrival in the city himself, Martin straddles the rural and urban divide: his visions of life are often seen through the side-mirror, peering into a past that he lived in the village.

The uncertainty that abounds as Paulina navigates the city’s labyrinth reflects the anxieties that roil the land. For a while, Martin’s heavy-handedness procures her cooperation, but does not quell her desire for self-reliance and self-discovery.

Paulina’s journey towards freedom appears promising: a short-lived affair produces a child that Martin was unable to sire, and her professional career is blooming. But just as politicians trade away the promises of independence, the nation implodes in a rictus of riots that subsume her private dream.

MacGoye’s vision of Kenya is prophetic and Coming to Birth remains a cautionary tale about this great land, whose promise is saddled with peril, prolonging birth pains of the nation-building project.

4. A Grain of Wheat by Ngugi wa Thiong’o - Of the several dozen texts produced by Kenya and Africa’s foremost author, Ngugi wa Thiong’o, A Grain of Wheat remains a favorite. Forming part of his foundational trilogy— others are Weep Not, Child, and The River Between—this novel evaluated what political independence heralded for ordinary citizens in Kenya.

The narrative unfurls in a space of ten days before Independence celebrations in 1963, and captures the anxieties that linger as each group reviews what has been lost, and gained, as black majoritarian rule succeeds colonialism.

Echoes of Kenya’s freedom struggle pulsate through the book, as do the heroic deeds of ordinary folks in defense of their land against the Brits. The dominant narrative is that of Mugo, a hermit that locals mistake for a freedom hero, but who is privately burdened by troubles of his own. His unraveling signals the novel’s denouement.

What’s remarkable about this novel is that its political message does not compromise its artistic sophistication—as some critics lament of Ngugi’s subsequent offerings. The characters are complex and well-developed, the storyline unpredictable and absorbing.

From his lengthy and productive literary life, lasting more than half a century, A Grain of Wheat is an example of Ngugi at his finest.

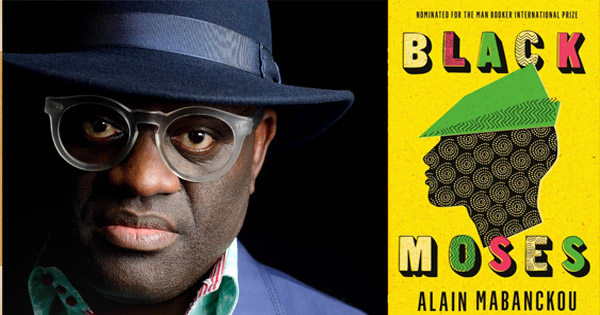

Alain Mabanckou

Photo Credit: Hermance Triay

Mabanckou's wacky, vibrant Black Moses, a small book with a big narrative voice, follows the adventures of an orphan who journeys to the city of Pointe-Noire, Republic of the Congo, where he strikes out on a last noble and violent quest. Mabanckou, who was born in Congo in 1966, selects an investigation of the Rwandan genocide and a short story collection that bridges the Atlantic.

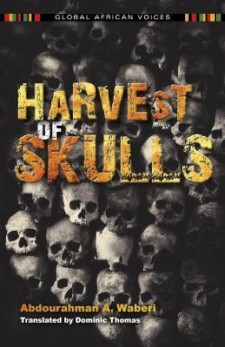

5. Harvest of Skulls by Abdourahman A. Waberi - Harvest of Skulls revisits the genocide that took place in Rwanda in 1994 that resulted in more than a million deaths. Franco-Djiboutian author Abdourahman Waberi, one of francophone Africa’s leading voices, visited Burundi and Rwanda on several occasions in the aftermath of the genocide under the aegis of the Writing by Duty of Memory project, an initiative launched by the Fest’Africa Festival. Waberi’s book delivers an original narrative that is at the same time a journey through a turbulent continent.

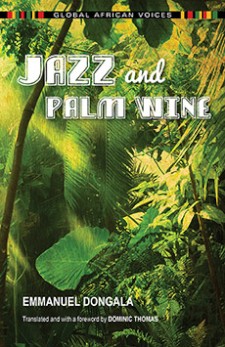

6. Jazz and Palm Wine by Emmanuel Dongala - This collection of short stories, considered a classic work of African literature by the Congolese writer Emmanuel Dongala, is situated on both sides of the Atlantic. Navigating between Africa and America, from the Communist experiments and ideals that defined the early years of political independence, considerations of the impact of brutal and repressive dictatorships, African mysticism, to the trials and tribulations of African America during the 1960s, framed in a profound fascination for jazz music in which the author finds equilibrium and salvation.

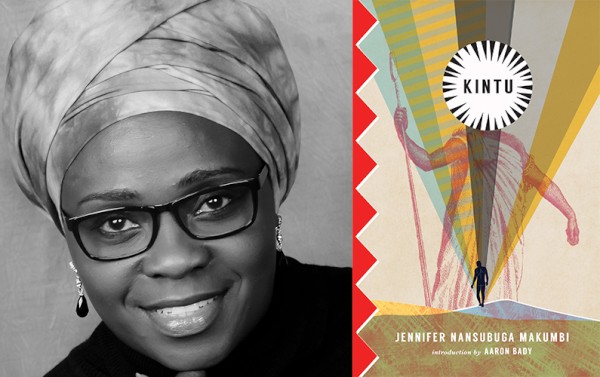

Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi

Makumbi's sweeping epic, Kintu, explores her native Uganda’s national identity through a brilliant interlacing of history, politics, and myth, tracing a curse on a family bloodline through the centuries. Her picks are Chinua Achebe's classic as well as Ben Okri's Man Booker-winning novel.

7. Things Fall Apart by Chinua Achebe - It should be frustrating for new writers like me to watch this novel hog the limelight year after year. Whenever a new writer pops up, the West proclaims a new Achebe: a recycling of talent, if you ask me. Recently, on the way back from Ake Festival, Ngugi wa Thiong'o remarked that he reads the text every year but it still manages to surprise him. Ezra Pound came to mind: Literature is news that stays news. However, there was a time, in the 1980s, when it seemed like the novel would not survive feminist indictment. Florence Stanton asked how things could fall apart for women who were “systematically excluded from the political, the judicial and even the discoursal life of the community?” But then Post-colonial investigation intensified and the novel repositioned itself. Recently, I read it through masculinities and queer lenses: guess what? Way back in the 1950s, Achebe was not just exploring transgressing masculinities, he was examining the deep fear of and persecution of femininity. Sorry, Stanton: it’s a feminist novel after all. The anonymous “things” in the title will keep propelling this novel long after you and I are forgotten, tsk!

8. The Famished Road by Ben Okri - In the current atmosphere of anti-migration in the world—the rise of the far-right in Europe, Brexit in Britain, Trump in the U.S., and xenophobia in South Africa—one wonders whether Azaro, the Abiku in Ben Okri’s The Famished Road, would still migrate from spirit to human realm. Abiku are spirit children whose life cycles through birth, death, and rebirth. It is a game they play on their human parents. However, out of love of his mother, Azaro has defected; he does not die. His spirit companions, enraged, torture him relentlessly. But Azaro has also given up a spirit world of magical beauty, a world that transcends geographical, racial, and cultural restriction, where mythical figures from different cultures coexist for a life circumscribed by race, place, and culture. He lives in a single room in a slum in Nigeria. Okri remains incisive on human inadequacies and the bullying of younger nations by developed ones.

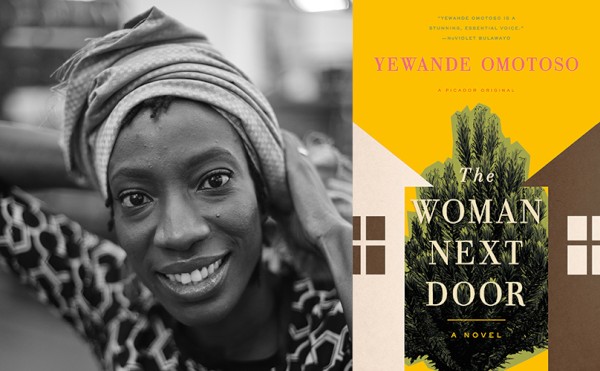

Yewande Omotoso

Photo Credit: Victor Dlamini

In Omotoso's charming and incisive The Woman Next Door, two Cape Town women, one black and one white, are neighbors who discover after 20 years of exchanging digs and insults that they might help each other. Omotoso, who has lived in South Africa since 1992, picks Sefi Atta's novel about a woman returning home from London to Lagos, and Fiston Mwanza Mujila's haunting Tram 83.

9. A Bit of Difference by Sefi Atta - There is a way in which the details of this book imbue all the characters, from the major to the walk-ons, with an exuberance that means they live beyond the page. After living in London for many years and working as a financial expert for an international charity, 39-year-old Deola Bello returns home to her ultra-wealthy family in Ikoyi, Lagos, on the occasion of her father’s five-year memorial service. But there is also a listlessness to her life that makes the homecoming all the more portentous. The novel seems to move on the engine of anecdotes. Back home, Deola’s mother nags her about the lack of grandchildren; through the lives of Deola’s sisters-in-law we observe the sober realities of patriarchy. In a precise and blistering scene, Atta gives a picture of the Lagos elite: "Nigeria is where they are called 'Madam' and treated with respect. They pass on their sense of entitlement to their children through estates. They are Nigerian Tories." The tone is wry, often caustic, but also humorous and moving. I enjoyed the unabashed presence of opinions and I got the sense that Atta doesn’t feel the need to disguise ideas and debate in fiction, that for her (and I am thankful for this) they are one and the same.

10. Tram 83 by Fiston Mwanza Mujila - Tram 83 is a bar in an unnamed African country, possibly Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo. A bar to rival all bars, perhaps the most intriguing and heart-breaking of bars I’ve ever come upon in a novel. At the entrance to the watering hole is a sign: “ENTRY INADVISABLE FOR THE POOR, THE WRETCHED, THE UNCIRCUMCISED, HISTORIANS, ARCHAEOLOGISTS, COWARDS, PSYCHOLOGISTS…” and the list continues. This novel is full of lists, repeated unanswered questions and really long sentences. There is a playfulness in the words, an effective carelessness that reveals the painstaking poet. The story of two friends, Lucien the writer and Requiem the crook, is told through their antics and conversations, the style frenetic. You could read Tram 83 as a ridiculous comedy or as a Kafkaesque tale. You could read it as bleak political commentary, that the “City-State,” somewhere beyond, has failed but also the world has failed, and people (men) come to Tram 83 to recover from their "bogus lives." I was abraded by the fact that nearly all the women in the story are selling their bodies, only ever (thinly and rather brutally at that) characterized as the purveyors of sex. Beyond the brilliant and seductive riffs, I found this story problematic at times but also satisfyingly haunting in its juggling of depravity and hope.

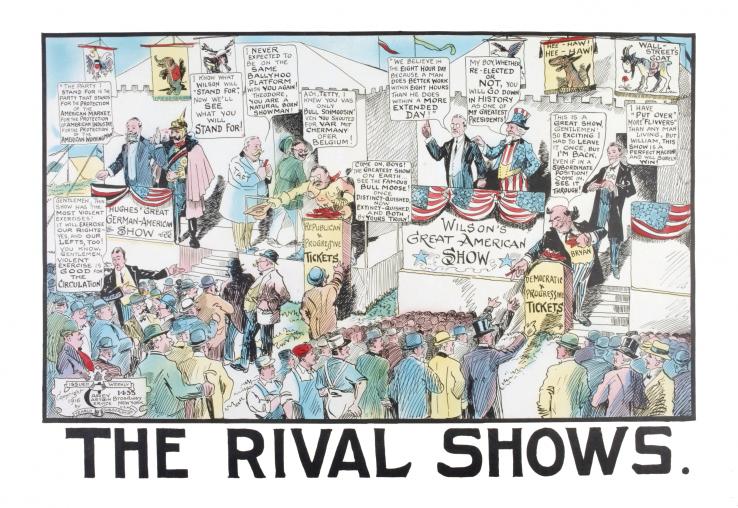

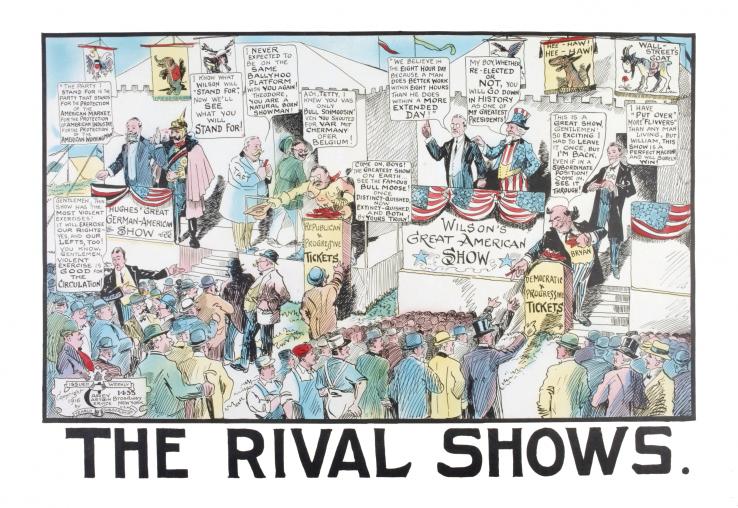

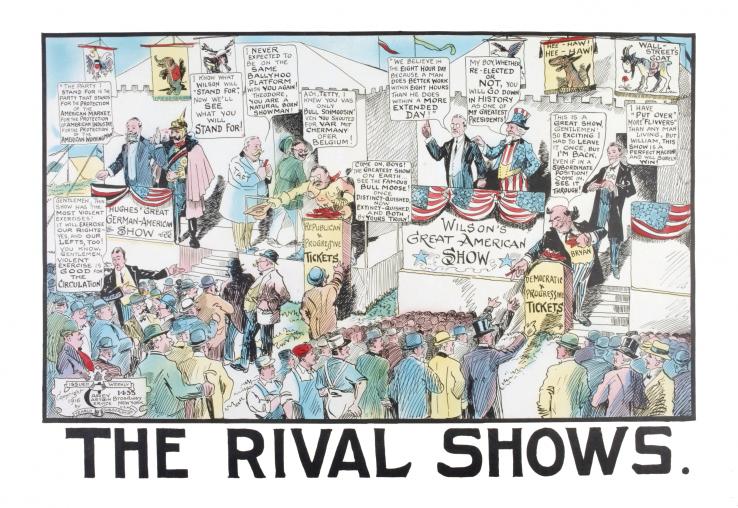

Constitution Under threat through ages. The Crisis of the Middle-Class Constitution: Why Economic Inequality Threatens Our Republic Hardcover – Deckle Edge, March 14, 2017 by Ganesh Sitaraman (Knopf) ;Examples & Explanations: Constitutional Law: National Power and Federalism (Examples & Explanations)Jan 8, 2016 by Christopher N. May and Allan Ides Paperback (Wolters Kluwer);Emanuel Law Outlines: Constitutional Law 34th Edition by Steven L. Emanuel ; The Constitution of the United States of America with the Declaration of Independence Paperback – June 7, 2017 by United States ( Barnes & Noble Books);White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of Our Racial Divide Hardcover – Deckle Edge, May 31, 2016 by Carol Anderson (Bloomsbury);A Sovereign People: The Crises of the 1790s and the Birth of American Nationalism 1st Edition by Carol Berkin( Basic Books) ;America's Constitution: A Biography 1st Edition(PB) Edition by Akhil Reed Amar (Random House); The Constitution: An IntroductionJan 3, 2017 by Michael Stokes Paulsen and Luke Paulsen Paperback ( Basic Books);Everything You Need to Ace American History in One Big Fat Notebook: The Complete Middle School Study Guide (Big Fat Notebooks)Aug 9, 2016 by Workman Publishing and Lily Rothman (Workman Publishing Company)

The American Constitution is the oldest in the world, but appearances are deceiving. Over the past two centuries, the Supreme Court has given very different meanings to the grand abstractions and cryptic formulae of the Constitution, and in doing so has ratified a series of great transformations in American government. From age to age, the court’s decisions have revolutionised the relationships between the presidency and Congress, between the federal government and the states, and between the individual and the state.

We are reaching another crossroads. There hasn’t been a new appointment to the court since 1994, but this extraordinary period of stability is coming to an end. Eight of the nine justices are 65 or older, with the eldest well into his eighties. Chief Justice Rehnquist is suffering from a serious illness: even his recovery will not long defer the moment at which the court begins a sustained period of reconstruction.

A series of openings will force George Bush, the Senate and the American people to confront a new set of choices. When the last vacancies arose during the 1980s and early 1990s, liberalism was still a dynamic force on the court. But the last liberal justices retired more than a decade ago. Nobody on the bench is interested in reviving the strong egalitarianism of the 1960s, when the Warren Court was in its heyday. The present judicial spectrum ranges from moderate liberals to radical rightists, and Bush will be aiming to nominate candidates who will push the court’s centre of gravity further to the right.

There are two very different kinds of conservative. The worldly statesman, distrustful of large visions and focused on the prudent management of concrete problems has long been familiar. But Bush has more often relied on neo-conservatives with a very different temperament. They throw caution to the winds, assault the accumulated wisdom of the age, and insist on sweeping changes despite resistant facts. Law is a conservative profession, but it is not immune to the neo-con temptation. The question raised by the coming vacancies to the Supreme Court is whether American law will remain in conservative hands, or whether it will be captured by a neo-con vision of revolutionary change. The issue is not liberalism v. conservatism, but conservatism v. neo-conservatism.

The coming struggle over the Supreme Court has been gathering momentum for almost twenty years: the nomination battles over Robert Bork in 1987 and Clarence Thomas in 1991 were harbingers. But times have changed since these bitter contests. Bork was a cutting-edge neo-conservative of the 1980s, but his successors may well go far beyond him, striking down laws protecting workers and the environment, supporting the destruction of basic civil liberties in the war on terrorism, and engaging in a wholesale attack on the premises of 20th-century constitutionalism. Or then again, Bush may hesitate. Despite his professed admiration for neo-con jurists such as Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas, he may offer up genuine conservatives, such as Sandra Day O’Connor, who reject radical change as a matter of principle.

The job of the Senate is to make it clear to the American people which path the president is taking. Under the Constitution, the president’s judicial nominations are subject to the Senate’s ‘advice and consent’, and it deliberates under rules that give the minority party a special say. Unless 60 of the 100 senators agree to terminate debate, a minority can block a final vote by refusing to end discussion of the nominee on the floor. If, in other words, the Republicans cannot muster 60 votes to bring a minority filibuster to a halt, the president will be obliged to withdraw his nomination.

The stakes are very high and the Democratic minority should be careful. In the first instance it should determine whether the president has nominated a traditional conservative or a radical neo-con. Above all else, it must oppose any ‘stealth’ candidate whose record is so undistinguished that his judicial philosophy remains secret. Perhaps after hearing a neo-con nominee present his arguments before the Senate judiciary committee most Americans will support the case for radical change; perhaps not. But one thing should be clear: the Senate should not give its ‘advice and consent’ to a stealth revolution in constitutional law.

Constitutional law is a crowded field in America, and it might seem surprising that a president could pass over leading figures and nominate a cipher to the Supreme Court. But this is all too realistic a prospect. Clarence Thomas was a stealth appointment, and his performance on the bench reveals the remarkably destructive potential of neo-conservatism. A healthy constitutional system learns from its mistakes. The Senate didn’t really know what it was getting in Thomas: it has an obligation to prevent another stealth candidacy this time around. The story of stealth appointments and how they became attractive is an interesting one. It begins with President Reagan’s victory in 1984. During his first term, Reagan selected the conservative O’Connor, but his landslide re-election encouraged a frontal assault on the liberal judicial legacy. The retirement of Chief Justice Burger created the opportunity: Reagan promoted William Rehnquist to the chief justiceship, selecting Antonin Scalia as his replacement on the bench. Senate Democrats reacted sharply, but aimed their fire at the wrong target: in trying, and failing, to deprive Rehnquist of his (symbolic) promotion, they gave the neo-con Scalia a free pass on a vote of 98 to zero.

Encouraged by this bait and switch, Reagan used his next vacancy to confirm the triumph of neo-conservatism. Robert Bork was a distinguished scholar at Yale Law School before becoming a neo-con hero by firing the Watergate prosecutor Archibald Cox when other officials in the Justice Department refused to obey Richard Nixon’s order. He deliberately turned his Senate hearings into ‘a discussion of judicial philosophy’, with the aim of exposing the modern heresies that had brought the Warren and Burger Courts to such jurisprudential absurdities as Roe v. Wade. He proved astonishingly unconvincing. Bork’s defeat served only to confirm the breadth of popular support for the Warren-Burger Court’s interpretation of constitutional rights.

Reagan was a tough man to convince. He nominated yet another neo-con academic-turned-judge, Douglas Ginsburg, and challenged his antagonists to continue the struggle. But Ginsburg’s past use of marijuana caused a scandal, and Reagan reluctantly called it quits. He returned to the path of pragmatic conservatism with Anthony Kennedy, who passed through the Democratic Senate without resistance.

Wishing to avoid another decisive neo-con defeat, George H.W. Bush developed the art of the stealth candidate. The search was on for neo-cons whose public statements and writings were so insubstantial that they could not be Borked. Stealth has its own dangers. Bush thought he had a neo-con in David Souter, but he had been misinformed. He did a better job the next time. Clarence Thomas had arrived in Washington at the age of 31, and never left the Beltway thereafter, so his neo-con development could be carefully monitored. At 43, he had put in loyal service as chairman of Reagan’s Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, but had avoided clear-cut pronouncements on most major issues.

Democrats bridled at the thought of Thomas as Thurgood Marshall’s successor, but, when interrogated, the nominee simply stonewalled. He stated, incredibly, that he had never expressed a view about Roe v. Wade in conversation with anyone, ever. When confronted with his signature on a tell-tale document denouncing abortion, he blandly denied reading it. The stealth technique was working until Anita Hill came forward with her claims of sexual harassment and the Democrats came out swinging with a politics of personal attack. Whether Anita Hill or Clarence Thomas was telling the truth isn’t relevant. My point is different: Bush’s stealth strategy was failing to solve the Bork problem. Rather than paving a smooth path to the court, it was causing an escalating spiral of partisan warfare and personal attack. Thomas won by a vote of 52 to 48, but the entire affair set the stage for the ugliest features of the politics of the 1990s. Character assassination had worked with Douglas Ginsburg, and it almost worked with Clarence Thomas: who would be next?

President Clinton did not want to find out. He filled two seats during his first two years in office, when Senate Democrats outnumbered Republicans by 56 to 44. But he refused to nominate a liberal version of Bork who would proudly pledge to bring back the Warren Court; nor did he try to push the court leftward with stealth candidates. He nominated two seasoned professionals – Ruth Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer – with track records as moderate liberals.

If Clinton had played a more provocative game, the Republicans would have responded in kind – ideological warfare, personal attacks and die-hard opposition. And perhaps they would have succeeded: their filibuster against Abe Fortas had forced Lyndon Johnson to withdraw his nomination as chief justice in 1968. But they were happy to accept Clinton’s olive branch, and readily confirmed his nominees. Both sides had been sobered up by the vicious cycles of the 1980s: constitutional evolution, not revolution, would be the order of the day.

Bush has three options when the next vacancy to the Supreme Court comes up: he can nominate a seasoned conservative, a stealth candidate or a plain-speaking neo-con. The president has one fewer senator than Bill Clinton had: 55 Republicans in 2005, 56 Democrats in 1993. But his strategic position is the same. He doesn’t have the 60 votes needed to override a determined filibuster by the opposition, so nominating a neo-con will be risky. Since no one can predict what will happen in Iraq, he may well come to regret a decision to precipitate another cycle of bitter partisan warfare on the home front.

Yet the image of Reagan beckons. His followers have never forgiven the Democrats for rejecting Bork. Shouldn’t Bush heed their call to complete the great work that Reagan began? The simple answer is no. The president should face some hard facts: his 3 per cent margin of victory over John Kerry doesn’t remotely resemble Reagan’s 18 point knock-out over Walter Mondale. Although 1984 marked a decisive victory over liberalism, last year’s election revealed that the most liberal candidate since Mondale was able to run neck-and-neck with an incumbent Republican. Despite his sweeping popular mandate, Reagan’s effort to revolutionise the court led to a cycle of character assassination from which we are only now recovering, and this is not the time to begin the cycle again.

All this seems obvious enough, but Bush has already established himself as one of the great gamblers in presidential history. He may well spurn the counsels of prudent statesmanship, and try to succeed where his father and his hero – not the same man – failed. This is the point where a stealth candidate becomes alluring. It promises Bush the chance to complete the neo-con revolution, without risking a Bork II disaster. If Bush does play the stealth card, the Senate Democrats should respond with an unconditional filibuster.

Stealth candidates are especially pernicious because today’s neo-cons have so much to be stealthy about. It is a grave mistake to suppose that Roe v. Wade exhausts their agenda. Sweeping constitutional revolution, taking in three different agendas – religion, anti-regulation and terrorism – is what they have in mind.

First, religion. Abortion remains a live issue, as Senator Arlen Specter recently learned when he almost lost his chairmanship of the Judiciary Committee by publicly cautioning the president against a cave-in to the religious right on the subject. But if Bush nominates a Bork II, it will rapidly become clear that neo-cons see Roe v. Wade as merely a symptom of a much deeper jurisprudential disease. They want to reject the long-standing view of the Due Process Clause which authorises the courts to protect the fundamental rights of Americans to ‘life, liberty and property’. So far as the neo-cons are concerned, the due process tradition is the handiwork of a cabal of activist judges, who have used the grant of ‘liberty’ to impose their liberal agenda on the nation.

This is a gross distortion. Over the course of the 20th century, the judicial champions of fundamental rights were the pre-eminent advocates of judicial restraint. Justice Felix Frankfurter reconstructed the libertarian foundations of due process doctrine after the New Deal, but was also the modern court’s foremost practitioner of restraint. He passed the torch to Justice John Harlan, an Eisenhower appointee who was the Warren Court’s fiercest critic during its heyday, but also wrote a brilliant opinion which laid the due process foundation for married couples to use contraceptives. As he explained, the court had, for generations, understood the ‘liberty’ protected by due process to include ‘a freedom from all substantial arbitrary impositions’. In his view, a state statute criminalising contraception ‘involves what, by common understanding throughout the English-speaking world, must be granted to be a most fundamental aspect of “liberty”, the privacy of the home in its most basic sense’. Since criminal trials centring on contraception would inevitably require the revelation of the most intimate details of marital life, Harlan joined the court in striking down such statutes. Harlan has died, but the due process tradition endures, and it has been conservative Republican appointees, not Democratic justices, who have taken the lead in further developing the implications of the due process right to privacy.

Looking at the broad range of cases, these conservative justices have been far more deferential to legislative decisions than Scalia and Thomas. Their defence of fundamental rights is part of a discriminating philosophy of judicial restraint. While leaving large areas open to democratic judgment, they have been unflinching in their defence of human freedom:

Had those who drew up and ratified the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth Amendment or the 14th Amendment known the components of liberty in its manifold possibilities, they might have been more specific. They did not presume to have this insight. They knew times can blind us to certain truths and later generations can see that laws once thought necessary and proper in fact serve only to oppress. As the Constitution endures, persons in every generation can invoke its principles in their own search for greater freedom.

This eloquent statement comes from Justice Kennedy, in the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Lawrence v. Texas, striking down criminal sodomy statutes that have stigmatised and oppressed homosexuals for centuries. Kennedy was Reagan’s substitute for Bork, and is no liberal. But in dissenting from Lawrence, Justice Scalia, joined by Rehnquist and Thomas, treats Kennedy’s centuries-old understanding of due process with contempt, as the ‘product of a court, which is the product of a law-profession culture that has largely signed up to the so-called homosexual agenda’.

Scalia forgets that all exercises in judicial interpretation are the product of a ‘law-profession culture’. Only the court’s openness to professional critique keeps it honest, and distinguishes it from an organ of naked political power. And his claim that the court has signed up to the ‘homosexual agenda’ is characteristically extreme: the majority held that the state could not throw gays into jail, striking down the laws of 16 states that continued this barbaric practice. It did not require the states to provide civil unions, much less marriage, leaving these issues to democratic deliberation. Scalia’s intemperate attacks should not blind us to the ultimate question that the Senate faces: whether the nominee’s interpretation of due process will deepen or trivialise the nation’s constitutional commitments to freedom and equality.

The religious community has much at stake in upholding the due process tradition. For example, the Constitution does not explicitly guarantee the right of religious families to send their children to church schools. In 1925 the Supreme Court used the Due Process Clause to strike down an Oregon statute shutting the state’s parochial schools. The court’s words in Pierce v. Society of Sisters are worth remembering: the Constitution’s ‘fundamental theory of liberty’, it explained, ‘excludes any general power of the state to standardise its children by forcing them to accept instruction from public teachers only. The child is not the mere creature of the state; those who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right, coupled with the high duty, to recognise and prepare him for additional obligations.’ The Scalia-Thomas rejection of the evolving due process tradition of liberty throws Pierce v. Society of Sisters into the dustbin of history along with Roe v. Wade and Lawrence v. Texas.

Some on the religious right may, however, choose to ignore their loss of fundamental rights since the neo-cons promise them a sweeping victory on a second front. The First Amendment declares that ‘Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion,’ and the modern Supreme Court has understood this broad provision to prohibit government from endorsing religion in American public life. Justice Scalia would repudiate this long-established principle. He agrees that the state can’t favour one religion over another, but he doesn’t think that it is an ‘establishment of religion’ if government supports religion in general. In making this claim, he fails to consider that Baptists and Buddhists have very different visions of God, and would argue fiercely over the meaning of ‘religion in general’. It doesn’t take a political prophet to predict that the Christian sects with the most votes will come out on top, leaving a trail of bitterness behind.

Justice Thomas goes even further. He denies that the Supreme Court has any authority to require the states to respect the anti-establishment principle. As he points out, the Establishment Clause originally applied only to the federal government. But in stark contrast to all other justices of the modern era, he refuses to interpret the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause, passed in the aftermath of the Civil War, as extending the anti-establishment principle to the states. On his view, there is nothing to stop Utah from making Mormonism into the state religion, so long as other sects retain the freedom to huddle together in their private conventicles.

Such extremism should serve as a red flag for senators of both parties. If the president’s nominee professes admiration for Clarence Thomas, he should explain how the outright establishment of religion is compatible with the religious and moral diversity of 21st-century America. Even Scalia’s position marks a radical departure from the constitutional consensus of modern times. Since ‘religion’ doesn’t exist apart from particular religions, Scalia’s view would authorise politicians to make countless theological judgments as they transformed the character of public education, the provision of public welfare and much else besides.

The neo-con religious agenda is nothing short of revolutionary. The modern Supreme Court has consistently barred the state from endorsing religion, and it has protected each American’s right to make intimate decisions about sexuality, child-bearing and child-rearing. Neo-cons would reverse these priorities; they would strip away the constitutional right to privacy, and empower politicians to engage in endless theological disputes.

Judicial revolutions have happened before. The ghost of Franklin Roosevelt haunts our present discontents. In seeking to catalyse a neo-con revolution, Reagan and George H.W. Bush were travelling down the path marked out by Roosevelt during the New Deal. The only difference is that they failed and Roosevelt succeeded. During his second and third terms, he appointed seven New Deal justices who transformed the reigning vision of the Constitution. The aim of the anti-regulatory agenda is to reverse this New Deal revolution and to turn the clock back to the days when the Old Court regularly struck down social welfare legislation.

Under the Constitution, the Congress is granted a series of enumerated powers, and for centuries, constitutionalists have debated the extent to which it is up to Congress, or the Supreme Court, to decide when legislation goes beyond the scope of these limited powers. Before the New Deal, the court intervened aggressively to keep Congress in check. The great source of contestation was the provision granting Congress the power to regulate ‘commerce among . . . the several states’. The Old Court interpreted this broad phrase in a highly restrictive fashion. For example, when Congress banned the products of child labour from interstate commerce, it took a harsh view of this morally compelling act. The Commerce Clause, the court explained, could not be used as a platform for regulating labour conditions within the states, because they involved ‘manufacturing’, not ‘commerce’, and on the basis of this wordplay, the statute was held to be unconstitutional. Child labour could be controlled only by the states.

In case the states took up this invitation too enthusiastically, the Old Court also restrained its efforts to control free-market abuses. In contrast to the federal government, the states can regulate anything they like, but they can’t violate the rights protected by the Constitution. The Old Court interpreted these to include freedom of contract, and in 1905, famously invalidated a state law limiting the working week to 60 hours. Under its notorious Lochner decision, it was more important to protect the sweatshops’ freedom of contract than the state’s interest in protecting workers’ health. These laissez-faire rights remained basically intact until they were swept away by the seven Roosevelt appointees.

Roosevelt did not make his revolution through stealth nominations. By the time he filled his first vacancy with Hugo Black in 1937, the New Deal was already in place: 76 out of 96 Senators were Democrats, and even some of the Republicans were liberals. The laissez-faire ideal had been thoroughly discredited by democratic politics, and the Roosevelt Court reinterpreted the Constitution to express this fundamental change in public opinion. By the early 1940s, it had unanimously repudiated restrictive precedents and transformed the Commerce Clause into a source of plenary Congressional power. Over the longer haul, it weakened, but did not eliminate, constitutional protections for private property and freedom of contract. Neo-cons seek to restore the ‘Constitution in Exile’ as it existed before the Roosevelt Revolution. We owe this phrase to Douglas Ginsburg, the federal judge whose nomination was withdrawn in the wake of Bork’s defeat. Writing in 1995, Ginsburg confessed that he did not expect to see the exile return during his lifetime, but he proposed its restoration as a long-term goal.

The Rehnquist Court has already laid some of the groundwork. After more than a half-century in which Congress was free to interpret the Commerce Clause to authorise legislation against any problem of national concern, the Supreme Court began in 1995 to place limits on its regulatory powers. Returning to ‘first principles’, a five to four majority in the Lopez case struck down Congress’s Safe Schools Act, which made it a crime to carry a gun within a school zone. As the dissenters pointed out, Lopez was an easy case under New Deal principles. The nation’s economic future obviously depends on its schools, so why can’t Congress forbid their disruption by gun-toting hoodlums? While schools may be local, their graduates move throughout the nation, and use their skills in interstate commerce. So where is the problem under the Commerce Clause? Chief Justice Rehnquist responded with the wordplay that led the Old Court to strike down progressive legislation. He treated ‘education’ as if it existed in an entirely different sphere from the ‘economic’ activities governed directly by the Commerce Clause. He then denied that unsafe schools even had a ‘substantial effect’ on commerce, ignoring the compelling demonstration supplied by the dissenters. Justice Thomas’s separate concurrence went further, condemning the New Deal Court’s switch as a ‘wrong turn’.

The Lopez case was only the beginning. The same five-judge majority has been nibbling around the edges of national power, escalating its attack with the Morrison decision of 2000. For the first time in modern history, Morrison struck down a civil rights statute, the Violence against Women Act, as beyond the powers of Congress. To reach this result, the court was obliged to narrow the meaning of another great clause of the Constitution. After the Civil War, the 14th Amendment committed the nation to the ‘equal protection of the laws’, and explicitly granted Congress the power to ‘enforce’ this promise of equality. Violence against women perpetuates their subordination, yet the same five to four majority denied that the 14th Amendment authorised Congress to take steps against this abuse. In striking down the statute, the majority ignored historical evidence that the framers of the 14th Amendment expected Congress, not the court, to take the lead in fighting inequality. Though neo-cons profess faith in the original understanding of the Constitution, their faith mysteriously runs out when it comes to civil rights.

It is premature to view these recent judgments as heralding the decisive return of the Constitution in Exile. Justice Thomas regularly writes separate concurring opinions elaborating on the most reactionary implications of the court’s most provocative paragraphs. But he speaks only for himself. The two old-fashioned conservatives in the five-judge majority – Kennedy and O’Connor – sometimes explicitly restrict their decisions to the narrow facts of particular cases. And sometimes they simply disagree with the neo-cons, joining more moderate justices in majority opinions that swerve back to more expansive interpretations of the Commerce and Equal Protection Clauses. Only the appointment of more neo-cons will resolve the present uncertainty, and make possible a full-scale ideological assault on the regulatory competences of the federal government.

An obvious victim would be the health and safety of workers. As Thomas might put it, before its ‘wrong turn’ in the 1930s, the court found federal child-labour laws beyond the power of Congress, and these old precedents could readily provoke a neo-con majority to reassess a great deal of modern protective legislation. The new court would probably be prudent enough not to attack these laws immediately. It would begin slowly by construing health and safety statutes narrowly in the light of its newly discovered constitutional doubts about their conformity with the Commerce Clause; a few years later, these doubts would ripen into a strong conviction that the Congresses of the late 20th century had entered forbidden ground reserved to the states.

Environmental law provides an even more tempting target. In protecting fragile ecosystems, the Endangered Species Act serves long-term economic interests in helping to prevent environmental catastrophe. But such long-term appeals no longer satisfy the court, as the Lopez decision showed in its rejection of Congress’s power to keep guns out of public schools. It would be child’s play for a neo-con majority to strike down the Endangered Species Act as beyond the Commerce Clause.

What’s more, the same five to four majority has been expanding the constitutional provision that guarantees ‘just compensation’ when property is ‘taken’ from its owners by the government. Neo-cons don’t limit this requirement to cases in which property is literally ‘taken’ away. Despite their professions of ‘strict construction’, they increasingly insist on compensation when environmental regulations restrict property-owners’ freedom to build on their land. If this trend continues, governments will be obliged to pay crippling amounts of money if they hope to protect the environment against free market exploitation.

Constitutional experts are well aware of these trends, but the word hasn’t reached the general public. While labour and environmental activists don’t look on the current Supreme Court as a friend, they don’t appreciate how much of an enemy it threatens to become. If Bush moves forward with Bork II, there will be far more at stake than the future of Roe v. Wade.

The key to the Constitution in Exile decisions are Kennedy and O’Connor, who have voted with the neo-cons to create a narrow five to four majority. In other important areas, one or both have joined the rest of the court to stop the anti-regulation agenda in its tracks. The court has recently and most notably reaffirmed the use of well-crafted affirmative action programmes by a vote of five to four, and upheld new statutory restrictions on large political contributions by the same margin. These results will change with a further shift to the right: there will be no affirmative action, and there will be a dramatic cut-back on permissible controls over campaign slush-funds.

During the 20th century, the federal government has become a general problem-solver, capable of responding flexibly to new issues as they come onto the horizon. The anti-regulation agenda is so broad that it threatens to destroy this familiar understanding of national government, forcing Congress to accept the invisible hand of the free market.

Both the religious and the anti-regulation agendas have long histories and intricate – if competing – judicial philosophies. The war on terrorism is a different matter, raising big questions that run across the grain of old philosophies. It’s no surprise, then, that the Supreme Court responded uncertainly when confronting its first three terrorism cases last term. It has been justly praised for rejecting the president’s effort to insulate Guantanamo from all judicial review. But it didn’t go further and explain which concrete safeguards would be required, leaving this to future litigation. And by a five to four vote, it refused to say anything at all about an even more important case involving Jose Padilla.

Padilla is an American citizen who has never fought on a traditional battlefield. He converted to Islam when in prison and later travelled to Pakistan. On returning to O’Hare Airport in Chicago, he was seized as a terrorist. Rather than proving the government’s case in court, the president declared him an unlawful combatant in the war against terrorism, stripped him of all his rights, and detained him indefinitely in a military prison. Padilla’s lawyer sought to gain his freedom by means of a writ of habeas corpus, but the president denied that federal courts could review his decisions as commander in chief.

The stakes are enormous: if the president can throw Padilla into jail on his say-so, no citizen is safe. After spending more than two years in confinement, Padilla finally got his case to the Supreme Court. But a majority seized on a jurisdictional pretext that will require him to wait another year or two while his case takes another detour in the lower courts. It’s a dark day when a citizen must wait in prison for three or four years before the court will even consider whether the government must prove its case against him in a court of law.

The court did come to a final judgment in another terrorism case. Yasir Hamdi is also an American citizen but was picked up on the battlefield in Afghanistan – a far more suspicious place to be than O’Hare Airport. His lawyers said that he was an inexperienced aid worker caught in the wrong place at the wrong time, but the government claimed that he was ‘affiliated with a Taliban unit’. Once again, the president denied that any court could review his findings as commander in chief. Only one justice agreed: Clarence Thomas. The rest of the court insisted that due process required concrete safeguards against arbitrary presidential detention. Yet they spoke with a multiplicity of voices, and settled on a dangerously low standard of review. Most important, Hamdi won’t be able to require the government to persuade a jury that he is guilty beyond a reasonable doubt. Instead, the court gave the government the benefit of the doubt, and will require Hamdi to prove his innocence before a military, not a civilian tribunal.

Hamdi v. Rumsfeld is limited to the treatment of Americans who are caught up in a traditional war. Nobody can say whether it will be extended to Padilla’s case when it returns to the Supreme Court. There is an obvious difference between seizing an American citizen on the battlefield, and seizing him at O’Hare Airport. But will a majority have the courage to draw the line, or will it allow the president to strip any citizen of his presumption of innocence by declaring him a foot-soldier in the war on terrorism? I fear the answer, especially if Padilla’s case returns to the court in the aftermath of another terrorist attack.

Bush’s favourite stealth candidate may well be an administration lawyer who has, in one way or another, helped construct the president’s extreme arguments for expanded powers as commander in chief. Consider the successful nomination of Jay Bybee to the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. Bybee was the assistant attorney general responsible for the preparation of the notorious torture memos which denied, for example, that Congress could constitutionally forbid the president from ordering the torture of enemy combatants. When they were leaked, the furor forced the administration to repudiate some of its most extreme positions. But the news came too late: Bybee had already been confirmed by the Senate. At the crucial moment, when questioned, he stonewalled: ‘As a member of the administration, it is my responsibility to support the president’s decision. To the extent that I might have a different personal view on this matter (or any other matter of administration policy), it would be inappropriate for me to express publicly a personal view at variance with the president’s position.’

If a nominee for the Supreme Court says something similar, the Democrats should invoke their power, under Senate rules, to continue the floor debate indefinitely until the nominee responds fully and frankly. Rather than promoting a Bush loyalist in the war on terrorism, the Senate should insist that the president bring forward one of the countless conservatives who have publicly defended the great American tradition of due process of law.

Suppose that Democrats allow the Senate to confirm two or three stealth nominees who secretly endorse all the positions presently advanced by Thomas in his separate opinions. Reinforced with the youthful energy of these true believers, the Bush Court will embark on a great revolution in constitutional law, and it is easy to imagine the likely future.

The court grants the president the power to strip citizens of their presumption of innocence, but doesn’t look on the powers of Congress with equal indulgence. The commander in chief makes war on his own citizens, but Congress is prevented from passing the Endangered Species Act. Sceptical of progressive health and safety regulation, the court requires that each initiative be tested rigorously to determine whether it has a ‘substantial effect’ on interstate commerce, and it is the court, and not Congress, that makes the crucial fact-finding decisions.

Americans are stripped of their constitutional rights to privacy, and women die in back-alley abortions. The state may snoop for tell-tale signs of forbidden intimacies or terrorist sentiments, but must protect property rights against intrusive zoning. If environmental concerns prompt a state or local government to take serious action, it must pay top dollar for the privilege. The court is careful to guarantee formal equality to blacks and other minorities, but if Congress wishes to act against the social forces keeping them down, the court will keep it on a very short leash: if protecting women against violence is beyond the power of Congress, its remedial powers are limited indeed. And yet the court’s fealty to limited government has its limits. It frees the states enthusiastically to support religion and authorises Congress to support these crusades with multi-billion dollar appropriations. The Establishment Clause merely restrains Congress from preferring Christians over Muslims in the struggle against secular humanism. While the court shrinks the scope of the Establishment Clause, it expands another provision of the First Amendment. ‘Freedom of speech’, it will tell us, guarantees rich people the right to give virtually unlimited political contributions.

All this will become clear at the Senate hearings, so long as the president is denied the stealth option, and comes forward with Bork II. At best, Republican apologists will seek to minimise the breadth of the neo-con revolution by making a short-term strategic point. Rehnquist is likely to provide the first vacancy, and his replacement by Bork II won’t change many five to four decisions in the short run. This point may encourage Democratic fence-sitters to confirm Bork II and delay a Senate filibuster until Bush tries to replace a more moderate justice with another neo-con.

This would be a fatal mistake. As soon as Bork II ascends to the Supreme Court, neo-cons will be crowing about their famous victory. Just as Reagan’s success in appointing Scalia encouraged the nomination of the more extreme Bork, the ascent of Bork II will encourage the nomination of a more extreme Bork III. In any event, it is wrong to succumb to a short-term perspective. The fate of the court depends on the success of progressives in convincing the country that the neo-con Constitution is wrong in principle. Once Senate Democrats concede that Bork II’s vision is acceptable, it will be very difficult for them to regain the initiative in future debates. The time for principled opposition is now.

We are reaching another crossroads. There hasn’t been a new appointment to the court since 1994, but this extraordinary period of stability is coming to an end. Eight of the nine justices are 65 or older, with the eldest well into his eighties. Chief Justice Rehnquist is suffering from a serious illness: even his recovery will not long defer the moment at which the court begins a sustained period of reconstruction.

A series of openings will force George Bush, the Senate and the American people to confront a new set of choices. When the last vacancies arose during the 1980s and early 1990s, liberalism was still a dynamic force on the court. But the last liberal justices retired more than a decade ago. Nobody on the bench is interested in reviving the strong egalitarianism of the 1960s, when the Warren Court was in its heyday. The present judicial spectrum ranges from moderate liberals to radical rightists, and Bush will be aiming to nominate candidates who will push the court’s centre of gravity further to the right.

There are two very different kinds of conservative. The worldly statesman, distrustful of large visions and focused on the prudent management of concrete problems has long been familiar. But Bush has more often relied on neo-conservatives with a very different temperament. They throw caution to the winds, assault the accumulated wisdom of the age, and insist on sweeping changes despite resistant facts. Law is a conservative profession, but it is not immune to the neo-con temptation. The question raised by the coming vacancies to the Supreme Court is whether American law will remain in conservative hands, or whether it will be captured by a neo-con vision of revolutionary change. The issue is not liberalism v. conservatism, but conservatism v. neo-conservatism.

The coming struggle over the Supreme Court has been gathering momentum for almost twenty years: the nomination battles over Robert Bork in 1987 and Clarence Thomas in 1991 were harbingers. But times have changed since these bitter contests. Bork was a cutting-edge neo-conservative of the 1980s, but his successors may well go far beyond him, striking down laws protecting workers and the environment, supporting the destruction of basic civil liberties in the war on terrorism, and engaging in a wholesale attack on the premises of 20th-century constitutionalism. Or then again, Bush may hesitate. Despite his professed admiration for neo-con jurists such as Antonin Scalia and Clarence Thomas, he may offer up genuine conservatives, such as Sandra Day O’Connor, who reject radical change as a matter of principle.

The job of the Senate is to make it clear to the American people which path the president is taking. Under the Constitution, the president’s judicial nominations are subject to the Senate’s ‘advice and consent’, and it deliberates under rules that give the minority party a special say. Unless 60 of the 100 senators agree to terminate debate, a minority can block a final vote by refusing to end discussion of the nominee on the floor. If, in other words, the Republicans cannot muster 60 votes to bring a minority filibuster to a halt, the president will be obliged to withdraw his nomination.

The stakes are very high and the Democratic minority should be careful. In the first instance it should determine whether the president has nominated a traditional conservative or a radical neo-con. Above all else, it must oppose any ‘stealth’ candidate whose record is so undistinguished that his judicial philosophy remains secret. Perhaps after hearing a neo-con nominee present his arguments before the Senate judiciary committee most Americans will support the case for radical change; perhaps not. But one thing should be clear: the Senate should not give its ‘advice and consent’ to a stealth revolution in constitutional law.

Constitutional law is a crowded field in America, and it might seem surprising that a president could pass over leading figures and nominate a cipher to the Supreme Court. But this is all too realistic a prospect. Clarence Thomas was a stealth appointment, and his performance on the bench reveals the remarkably destructive potential of neo-conservatism. A healthy constitutional system learns from its mistakes. The Senate didn’t really know what it was getting in Thomas: it has an obligation to prevent another stealth candidacy this time around. The story of stealth appointments and how they became attractive is an interesting one. It begins with President Reagan’s victory in 1984. During his first term, Reagan selected the conservative O’Connor, but his landslide re-election encouraged a frontal assault on the liberal judicial legacy. The retirement of Chief Justice Burger created the opportunity: Reagan promoted William Rehnquist to the chief justiceship, selecting Antonin Scalia as his replacement on the bench. Senate Democrats reacted sharply, but aimed their fire at the wrong target: in trying, and failing, to deprive Rehnquist of his (symbolic) promotion, they gave the neo-con Scalia a free pass on a vote of 98 to zero.

Encouraged by this bait and switch, Reagan used his next vacancy to confirm the triumph of neo-conservatism. Robert Bork was a distinguished scholar at Yale Law School before becoming a neo-con hero by firing the Watergate prosecutor Archibald Cox when other officials in the Justice Department refused to obey Richard Nixon’s order. He deliberately turned his Senate hearings into ‘a discussion of judicial philosophy’, with the aim of exposing the modern heresies that had brought the Warren and Burger Courts to such jurisprudential absurdities as Roe v. Wade. He proved astonishingly unconvincing. Bork’s defeat served only to confirm the breadth of popular support for the Warren-Burger Court’s interpretation of constitutional rights.

Reagan was a tough man to convince. He nominated yet another neo-con academic-turned-judge, Douglas Ginsburg, and challenged his antagonists to continue the struggle. But Ginsburg’s past use of marijuana caused a scandal, and Reagan reluctantly called it quits. He returned to the path of pragmatic conservatism with Anthony Kennedy, who passed through the Democratic Senate without resistance.

Wishing to avoid another decisive neo-con defeat, George H.W. Bush developed the art of the stealth candidate. The search was on for neo-cons whose public statements and writings were so insubstantial that they could not be Borked. Stealth has its own dangers. Bush thought he had a neo-con in David Souter, but he had been misinformed. He did a better job the next time. Clarence Thomas had arrived in Washington at the age of 31, and never left the Beltway thereafter, so his neo-con development could be carefully monitored. At 43, he had put in loyal service as chairman of Reagan’s Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, but had avoided clear-cut pronouncements on most major issues.

Democrats bridled at the thought of Thomas as Thurgood Marshall’s successor, but, when interrogated, the nominee simply stonewalled. He stated, incredibly, that he had never expressed a view about Roe v. Wade in conversation with anyone, ever. When confronted with his signature on a tell-tale document denouncing abortion, he blandly denied reading it. The stealth technique was working until Anita Hill came forward with her claims of sexual harassment and the Democrats came out swinging with a politics of personal attack. Whether Anita Hill or Clarence Thomas was telling the truth isn’t relevant. My point is different: Bush’s stealth strategy was failing to solve the Bork problem. Rather than paving a smooth path to the court, it was causing an escalating spiral of partisan warfare and personal attack. Thomas won by a vote of 52 to 48, but the entire affair set the stage for the ugliest features of the politics of the 1990s. Character assassination had worked with Douglas Ginsburg, and it almost worked with Clarence Thomas: who would be next?

President Clinton did not want to find out. He filled two seats during his first two years in office, when Senate Democrats outnumbered Republicans by 56 to 44. But he refused to nominate a liberal version of Bork who would proudly pledge to bring back the Warren Court; nor did he try to push the court leftward with stealth candidates. He nominated two seasoned professionals – Ruth Ginsburg and Stephen Breyer – with track records as moderate liberals.

If Clinton had played a more provocative game, the Republicans would have responded in kind – ideological warfare, personal attacks and die-hard opposition. And perhaps they would have succeeded: their filibuster against Abe Fortas had forced Lyndon Johnson to withdraw his nomination as chief justice in 1968. But they were happy to accept Clinton’s olive branch, and readily confirmed his nominees. Both sides had been sobered up by the vicious cycles of the 1980s: constitutional evolution, not revolution, would be the order of the day.

Bush has three options when the next vacancy to the Supreme Court comes up: he can nominate a seasoned conservative, a stealth candidate or a plain-speaking neo-con. The president has one fewer senator than Bill Clinton had: 55 Republicans in 2005, 56 Democrats in 1993. But his strategic position is the same. He doesn’t have the 60 votes needed to override a determined filibuster by the opposition, so nominating a neo-con will be risky. Since no one can predict what will happen in Iraq, he may well come to regret a decision to precipitate another cycle of bitter partisan warfare on the home front.

Yet the image of Reagan beckons. His followers have never forgiven the Democrats for rejecting Bork. Shouldn’t Bush heed their call to complete the great work that Reagan began? The simple answer is no. The president should face some hard facts: his 3 per cent margin of victory over John Kerry doesn’t remotely resemble Reagan’s 18 point knock-out over Walter Mondale. Although 1984 marked a decisive victory over liberalism, last year’s election revealed that the most liberal candidate since Mondale was able to run neck-and-neck with an incumbent Republican. Despite his sweeping popular mandate, Reagan’s effort to revolutionise the court led to a cycle of character assassination from which we are only now recovering, and this is not the time to begin the cycle again.

All this seems obvious enough, but Bush has already established himself as one of the great gamblers in presidential history. He may well spurn the counsels of prudent statesmanship, and try to succeed where his father and his hero – not the same man – failed. This is the point where a stealth candidate becomes alluring. It promises Bush the chance to complete the neo-con revolution, without risking a Bork II disaster. If Bush does play the stealth card, the Senate Democrats should respond with an unconditional filibuster.

Stealth candidates are especially pernicious because today’s neo-cons have so much to be stealthy about. It is a grave mistake to suppose that Roe v. Wade exhausts their agenda. Sweeping constitutional revolution, taking in three different agendas – religion, anti-regulation and terrorism – is what they have in mind.

First, religion. Abortion remains a live issue, as Senator Arlen Specter recently learned when he almost lost his chairmanship of the Judiciary Committee by publicly cautioning the president against a cave-in to the religious right on the subject. But if Bush nominates a Bork II, it will rapidly become clear that neo-cons see Roe v. Wade as merely a symptom of a much deeper jurisprudential disease. They want to reject the long-standing view of the Due Process Clause which authorises the courts to protect the fundamental rights of Americans to ‘life, liberty and property’. So far as the neo-cons are concerned, the due process tradition is the handiwork of a cabal of activist judges, who have used the grant of ‘liberty’ to impose their liberal agenda on the nation.

This is a gross distortion. Over the course of the 20th century, the judicial champions of fundamental rights were the pre-eminent advocates of judicial restraint. Justice Felix Frankfurter reconstructed the libertarian foundations of due process doctrine after the New Deal, but was also the modern court’s foremost practitioner of restraint. He passed the torch to Justice John Harlan, an Eisenhower appointee who was the Warren Court’s fiercest critic during its heyday, but also wrote a brilliant opinion which laid the due process foundation for married couples to use contraceptives. As he explained, the court had, for generations, understood the ‘liberty’ protected by due process to include ‘a freedom from all substantial arbitrary impositions’. In his view, a state statute criminalising contraception ‘involves what, by common understanding throughout the English-speaking world, must be granted to be a most fundamental aspect of “liberty”, the privacy of the home in its most basic sense’. Since criminal trials centring on contraception would inevitably require the revelation of the most intimate details of marital life, Harlan joined the court in striking down such statutes. Harlan has died, but the due process tradition endures, and it has been conservative Republican appointees, not Democratic justices, who have taken the lead in further developing the implications of the due process right to privacy.

Looking at the broad range of cases, these conservative justices have been far more deferential to legislative decisions than Scalia and Thomas. Their defence of fundamental rights is part of a discriminating philosophy of judicial restraint. While leaving large areas open to democratic judgment, they have been unflinching in their defence of human freedom:

Had those who drew up and ratified the Due Process Clauses of the Fifth Amendment or the 14th Amendment known the components of liberty in its manifold possibilities, they might have been more specific. They did not presume to have this insight. They knew times can blind us to certain truths and later generations can see that laws once thought necessary and proper in fact serve only to oppress. As the Constitution endures, persons in every generation can invoke its principles in their own search for greater freedom.

This eloquent statement comes from Justice Kennedy, in the Supreme Court’s recent decision in Lawrence v. Texas, striking down criminal sodomy statutes that have stigmatised and oppressed homosexuals for centuries. Kennedy was Reagan’s substitute for Bork, and is no liberal. But in dissenting from Lawrence, Justice Scalia, joined by Rehnquist and Thomas, treats Kennedy’s centuries-old understanding of due process with contempt, as the ‘product of a court, which is the product of a law-profession culture that has largely signed up to the so-called homosexual agenda’.

Scalia forgets that all exercises in judicial interpretation are the product of a ‘law-profession culture’. Only the court’s openness to professional critique keeps it honest, and distinguishes it from an organ of naked political power. And his claim that the court has signed up to the ‘homosexual agenda’ is characteristically extreme: the majority held that the state could not throw gays into jail, striking down the laws of 16 states that continued this barbaric practice. It did not require the states to provide civil unions, much less marriage, leaving these issues to democratic deliberation. Scalia’s intemperate attacks should not blind us to the ultimate question that the Senate faces: whether the nominee’s interpretation of due process will deepen or trivialise the nation’s constitutional commitments to freedom and equality.

The religious community has much at stake in upholding the due process tradition. For example, the Constitution does not explicitly guarantee the right of religious families to send their children to church schools. In 1925 the Supreme Court used the Due Process Clause to strike down an Oregon statute shutting the state’s parochial schools. The court’s words in Pierce v. Society of Sisters are worth remembering: the Constitution’s ‘fundamental theory of liberty’, it explained, ‘excludes any general power of the state to standardise its children by forcing them to accept instruction from public teachers only. The child is not the mere creature of the state; those who nurture him and direct his destiny have the right, coupled with the high duty, to recognise and prepare him for additional obligations.’ The Scalia-Thomas rejection of the evolving due process tradition of liberty throws Pierce v. Society of Sisters into the dustbin of history along with Roe v. Wade and Lawrence v. Texas.